Transcription Network Basics: Part One

Understanding the fundamental concepts of transcription networks

Let's say that in one of your cells, the membrane that houses the cell has been damaged. In order to fix it, your cell needs to produce repair proteins. How might it do so?

To answer this, let's first set up a simple framework, and then bit by bit, fill in the details. First, in order for your cell to begin creating repair proteins, it must know that your cell is damaged — it needs some kind of signal. Then, once it receives that signal, it can begin producing the repair proteins to fix the membrane. Easy enough.

But there's another step: after your cell has completed its repairs, it needs to know when to stop producing repair proteins. Protein production uses up valuable resources, so your cell probably shouldn't waste it creating repair proteins it doesn't need. Once the repairs are done, the cell can stop transmitting the repair signal, and as a result stop production.

So, we have a very simple framework so far: a cell receives a signal, begins producing corresponding proteins; stops receiving the signal, stops producing those proteins. Essentially, like a traffic light for protein production.

Proteins are encoded in genes, so when we talk about protein production, we're really talking about gene expression. In our simple model, the presence of a signal promotes gene expression, and its absence stops it. We can show this in a simple diagram:

Let's take a quick look into how gene expression works. A gene is a stretch of DNA that encodes a protein, normally represented in text by a series of bases: ACTAGCC, for example. An enzyme, RNA polymerase, attaches itself to a binding site just preceding the gene, and moves along the gene and uses the information to synthesize messenger RNA, or mRNA for short. This process is called transcription. The mRNA is transported to the ribosome, the cell's molecular factory, where it is used to synthesize — amino acid by amino acid — the new protein, in a process known as translation. The newly minted protein is then transported, either inside or outside the cell, where it can begin its job.

We can update our diagram to include some of these details:

It still illustrates the same process as the very simplified one above, but with the specific machinery that enable gene expression. There's a small part of the puzzle still missing: how the signal S plays a role here. We know, from the simple framework we set up above, that it should play the role of a switch: turn on gene expression when the signal is present; turn off gene expression when it's not.

The missing piece, the macromolecule that enables this switch-like functionality, is a special protein known as a transcription factor. Transcription factors can shift rapidly between an active and inactive state based on the presence (or lack thereof) of a signal. When active, they bind to DNA and regulate the rate at which genes are read, like a molecular valve. In effect, they play a very important role acting as a bridge between a signal and a change in protein production.

Let's update our diagram again. The first shows just the changes, the second is the fully labeled diagram:

This is a simple model of how a cell responds to a signal. Our example, membrane damage, is just one of the many signals cells can send to communicate changes in their environment. Higher temperature, an influx of nutrients or toxins, damage to DNA, and even signaling molecules from other cells (hormones are one example of this) all have their own signals that interact with transcription factors.

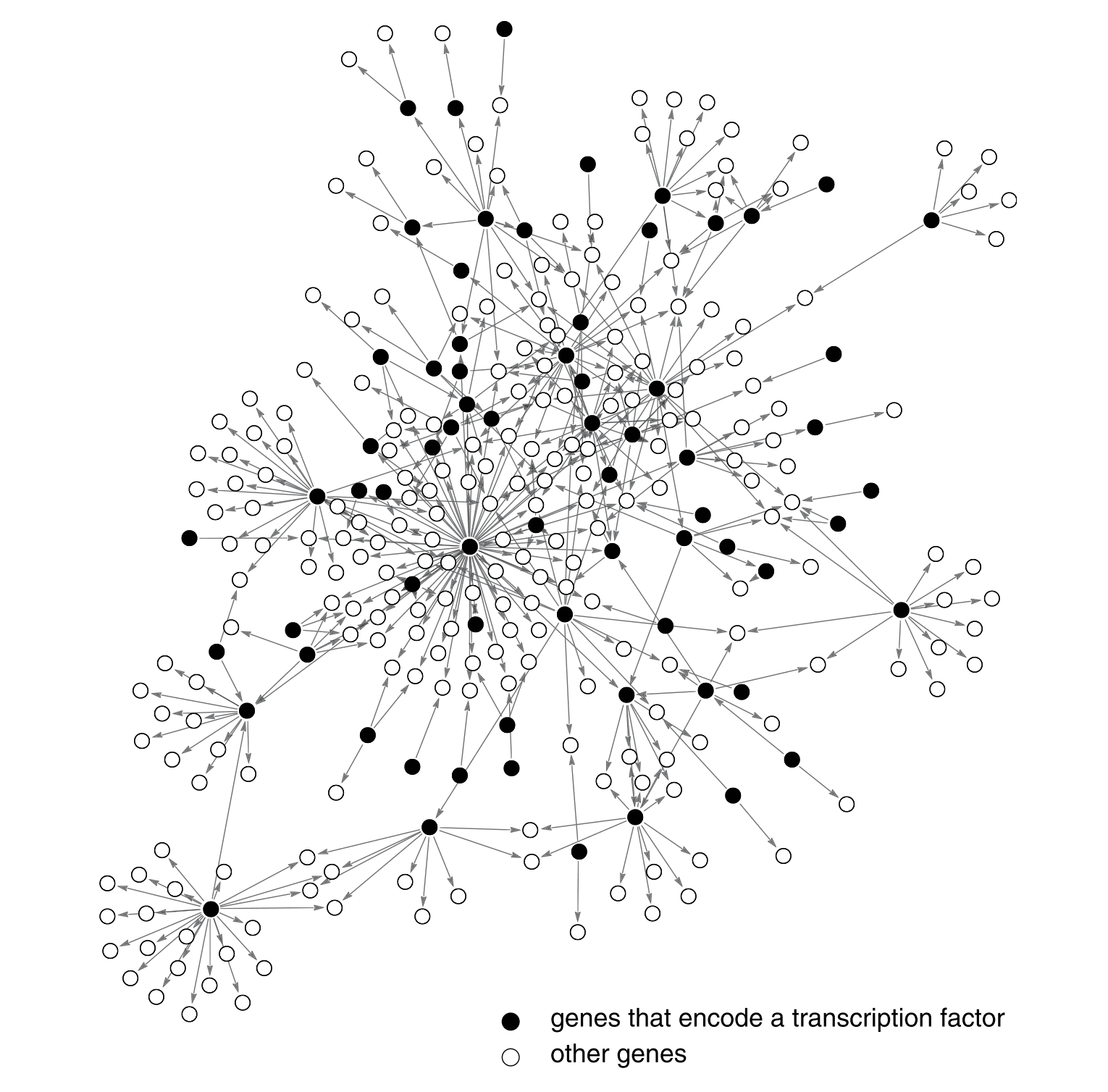

Transcription factors are also proteins, so they themselves are encoded in genes, which can be regulated by other transcription factors, which in turn can be regulated by other transcription factors, and so on. This creates a pretty complex set of interactions, and can be modeled as a network — transcription networks. As we will uncover in this series, combining transcription factors result in some very interesting properties and incredible solutions life has found for problems it faces. We'll explore how cells can respond instantly, or with a delay when necessary; how they can perform logical operations, their own version of OR and AND gates from computers; how different network structures keep showing up in different forms of life and how they give organisms an evolutionary advantage; how cells can create memory, and much, much more.

For now, I'll leave you with this picture of a transcription network that includes about 20% of the genes in E. coli. It's pretty complex, but we'll break them into smaller networks and find understandable patterns in this upcoming series. In Part Two, we'll learn about the two types of transcription factors, mathematically model increases or decreases in protein production, and take a closer look at what those arrows in the network represent.

If you liked this and would like to hear when new content is published, please subscribe below.

If you have any feedback, found bugs, or just want to reach out, feel free to DM me on Twitter or send me an email.

Subscribe to Newt Interactive

You'll only get emails when I publish new content. No spam, unsubscribe any time.